In the 1870s, the observation that the nuclei of male and female reproductive cells undergo fusion in the process of fertilization leads to the decision that the cell nucleus plays a key role in inheritance.

After that, when the cell is stained with the help of some when certain dyes under the light microscope chromosomes were first observed as visible inside the nucleus as thread-like objects. A characteristic “splitting” behavior of chromosomes was found in which each daughter cell formed by cell division receives an identical complement of chromosomes.

Soon thereafter, the observation that, whereas the number of chromosomes in each cell may differ among biological species, the number of chromosomes is nearly always constant within the cells of any particular species provided the evidence for the importance of chromosomes. Around 1900, these features of chromosomes were well understood and this information suggested that the chromosomes were the carriers of the genes.

By the 1920s, several lines of indirect evidence began to suggest a close relationship between chromosomes and DNA. Again DNA is present in chromosomes was showed by the microscopic studies with special stains. Various types of proteins are present in the chromosomes, but chromosomal proteins differ significantly from one cell type to another by the means of amount and type, whereas the amount of DNA per cell is constant. Nearly the total amount of DNA present in cells of higher organisms is observed inside the chromosomes. These arguments for DNA as the genetic material were unconvincing, however, because crude chemical analyses had suggested that DNA lacks the chemical diversity needed in a genetic substance.

As proteins were known to be an exceedingly diverse collection of molecules, it was strongly recommended as the genetic material. That’s why Proteins became widely accepted as the genetic material, and DNA was assumed to function merely as the structural framework of the chromosomes. The experiments described below finally demonstrated that DNA is the genetic material.

Experimental Proof of the Genetic Function of DNA

Griffth’s Experiment (1928)

An important first step was taken by Frederick Griffith in 1928 when he demonstrated that a physical trait can be passed from one cell to another.

The two strains of the bacterium

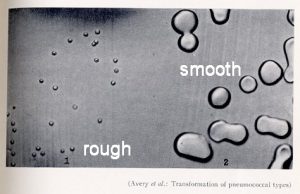

Streptococcus pneumoniae identified as S (virulent= capable of killing the host) and R (non-virulent). When a bacterial cell is grown on a solid medium, it undergoes repeated cell divisions to form a visible clump of cells called a colony.

A gelatinous capsule composed of complex carbohydrate (polysaccharide) synthesized by the S type of S. pneumoniae. Because of the enveloping capsule, each colony becomes large and gives its a glistening or smooth (S) appearance. This capsule also enables the bacterium to cause pneumonia by protecting it from the defense mechanisms of an infected animal. But the R strains of S. pneumoniae form small colonies that have a rough (R) surface because they cannot synthesize the capsular polysaccharide.

This strain of the bacterium does not cause pneumonia, because without the capsule the bacteria get inactivated by the immune system of the host.

Both types of bacteria “breed true” as because the progeny formed by cell division have the capsular type of the parent, either S or R.

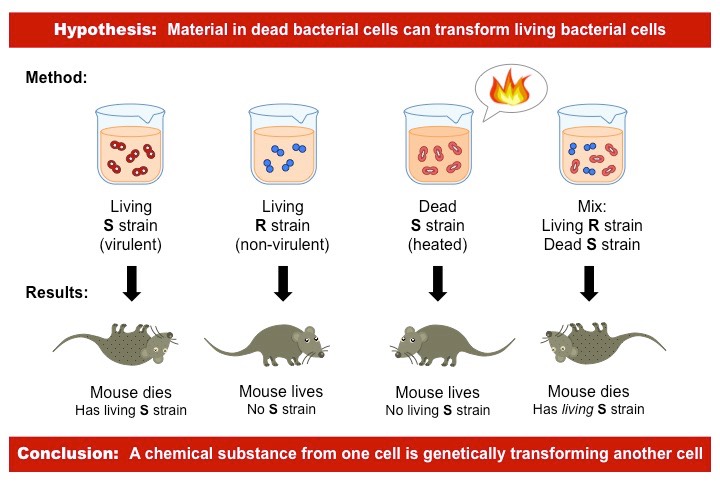

Observation

- Mice injected with living S cells get pneumonia.

- Mice injected either with living R cells remain healthy.

- Mice injected with heat-killed S cells remain healthy.

- The fourth observation was Griffith’s critical finding: mice injected with a mixture of living R cells and heat-killed S cells cause the disease—they often die of pneumonia. Bacteria isolated from blood samples of these dead mice contain virulent S cultures with a capsule typical of the injected S cells, even though the injected S cells had been killed by heat.

Conclusion

Evidently, the injected material from the dead S cells includes a substance that can be transferred to living R cells and confer the ability to resist the immunological system of the mouse and cause pneumonia. In other words, the R bacteria can be changed or undergo transformation into S bacteria. Furthermore, the new characteristics are inherited by descendants of the transformed bacteria.

Avery–MacLeod–McCarty Experiment (Bacterial transformation) (1924)

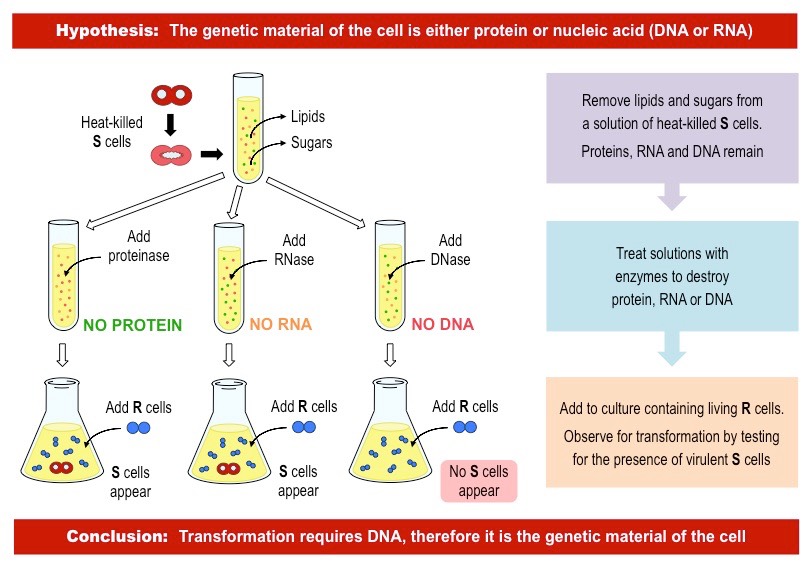

Transformation in Streptococcus was originally discovered in 1928, but it was not until 1944 that the chemical substance responsible for changing the R cells into S cells was identified. Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty showed that the substance causing the transformation of R cells into S cells was DNA which was a milestone experiment.

To perform this experiments, they first need to do some work which had never been done before such as they had to develop chemical procedures for isolating almost pure DNA from cells.

- They prepared cultures which contained the heat-killed S strain and after that they removed lipids and carbohydrates from the solution.

- Next, they treated the solutions with different digestive enzymes (DNase, RNase or protease) to destroy the targeted compound.

- Finally, they introduced living R strain cells to the culture to see which cultures would develop transformed S strain bacteria.

- Only in the culture treated with DNase did the S strain bacteria fail to grow (i.e. no DNA = no transformation)

- This indicated that DNA was the genetic component that was being transferred between cells.

Though it was a ground breaking finding but the scientific community disagree to accept the role of DNA as genetic material. Interesting thing is that only 8 years later, when Hershey and Chase conducted their experiment, that the concept gained popularity.

Refefence:

- Genetics: analysis of gene and genomes, By Daniel Hartl, Maryellen Ruvolo; 8th edition.

Revised by

- Md. Siddiq Hasan on 29 September 20

- Md. Siddiq Hasan on 30 November 20

Best safe and secure cloud storage with password protection

Get Envato Elements, Prime Video, Hotstar and Netflix For Free

Plantlet The Blogging Platform of Department of Botany, University of Dhaka

Plantlet The Blogging Platform of Department of Botany, University of Dhaka