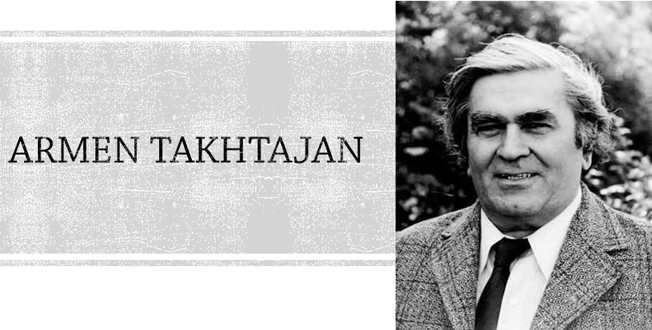

Present-day Armenian-born botanist & systematist Armen Leonovich Takhtajan (1910-2009) was one of the most influential figures of 20th century in the field of plant evolution, systematics, and biogeography. His other interests included morphology of flowering plants, paleobotany, and the flora of the Caucasus (region between the Black sea & the Caspian sea).

Good to know

- The standard author abbreviation Takht. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name. E.g. Gymnospermium odessanum (DC.) Takht.

- Despite great personal and professional risk, Takhtajan was a strong opponent of the theories of T. D. Lysenko, who had the support of Stalin and Krushchev in banning all teaching of genetics from the 1930s to the 1960s.

- With his wife Alice, he spent many happy and productive months as a guest researcher at the New York Botanical Garden (with his great friend Arthur Cronquist).

- He wrote 20 books and more than 300 scientific papers, many of which were ground-breaking.

He worked as a paleobotanist in Komarov Botanical Institue of Leningrad, USSR (present day Russia) of Russian Academy of Sciences. While working in the institute, Takhtajan in 1942 developed a classification scheme for flowering plants that emphasized phylogenetic relationships between plants.

This first attempt made the arrangement of classification up to the orders of higher plants, based on the structural types of gynoecium and placentation.

After 12 years i.e. in 1954, the actual system of classification was published in ‘The Origin of Angiospermous Plants’ in Russian language. It was translated into English in 1958 and thus came to the attention of the rest of the world. Further versions appeared in 1959 (Die Evolution der Angiospermen).

Later on, in 1966 (1964?), he proposed a new system of classification in Russian language (Sistema i filogeniia tsvetkovykh rastenii). The same classification was published in ‘Flowering Plants: Origin and Dispersal’ (1969) in English.

Later on, in 1980, a further revision of his system was published in ‘Botanical Review’.

To trace the evolution of angiosperm, he was particularly inspired by Hallier’s attempt to develop a synthetic evolutionary classification of flowering plants based on Darwinian philosophy.

Outline of Classification

The classification as proposed by Takhtajan treats flowering plants as a division (phylum) named Magnoliophyta, with two classes, Magnoliopsida (dicots) and Liliopsida (monocots). These two classes are subdivided into subclasses, and then superorders, orders, and families.

| Division | Class | Sub-class | Order |

| Magnoliophyta (Angiosperms) |

Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons) |

Magnolidae | 7 |

| Hamamelidae | 8 | ||

| Ranunculidae | 3 | ||

| Caryophyllidae | 3 | ||

| Dillenidae | 12 | ||

| Rosidae | 16 | ||

| Asteridae | 7 | ||

| Liliopsida (Monocotyledons) |

Alismatidae | 3 | |

| Lilidae | 3 | ||

| Arecidae | 5 | ||

| Commelinidae | 6 |

In the class Magnoliopsida,

- Most primitive order: Magnoliales

- Most advanced order: Asterales.

In the class Liliopsida,

- Most primitive order: Alismatales

- Most advanced order: Arales.

The Takhtajan system is similar to the classification scheme of Cronquist, but with somewhat greater complexity at the higher levels. Takhtajan favored smaller orders and families, to allow character and evolutionary relationships to be more easily grasped.

The Takhtajan classification system remains influential; it is used, for example, by the Montréal Botanical Garden.

Principles of Classification

| Character | Primitive | Advanced |

| Growth habit | Woody habit | Herbaceous habit |

| Small woddy angisoperm | Large trees of tropical rain forests | |

| Sparingly branched trees | Trees with numerous slender branches | |

| Evergreen plants | Deciduous woody plants | |

| Leaves | Simple leaves | Compound leaves |

| Reticulate venation | Parallel venation | |

| Alternate leaves | Opposite leaves | |

| Stomata | Mesogenous type | Peigenous type |

| With subsidiary cells | Lacking subsidiary cells | |

| Nodal structure | Tri to pentalacunar type | Unilacunar type |

| Inflorescence | Cymose | Racemose |

| Floral structure | Indefinite and variable number of floral parts arranged spirally on an elongated axis. | Fixed number of floral parts arranged in cyclic pattern on a short axis |

| Pollen grains | Exine devoid of external sculpturing | Sculpturing is of various types |

| Monocolpate (dicots) | Ticolpate (dicots) | |

| Gynoecium | Apocarpous | Syncarpous |

| Ovules | Anatropous ovule | Other types |

| Crassinucellate ovules | Tenuinucellate ovules | |

| Pollination | Entomophily | Anemophily |

| Gametophyte & fertilization | Monosporic Polygonum type | Tetrasporic type |

| Seeds | Abundant endosperm with a minute and undifferentiated embryo | Endosperm is reduced or wanting and the embryo is large and well differentiated |

| Fruits | Many seeded follicular fruit develop from multicarpellary apocarpous gynoecia. | Coenocarpous fruits |

Merits of Takhtajan’s classification

- The classification of Takhtajan is more phylogenetic than that of earlier systems.

- This classification is in a general agreement with the major contemporary systems of Cronquist, Dahlgren, Thorne, and others.

- Nomenclature adopted in this system is in accordance with the ICBN, even at the level of division.

- The treatment of Magnolidae as a primitive group and the placement of Dicotyledons before Monocotyledons are in agreement with the other contemporary systems.

- The concept of primitive flower in the classification is in accordance with modern taxonomists

-

The introduction of the rank of “super order” in the classification has provided an important link between the large ‘subclass’ and the smaller ‘order”.

Demerits of Takhtajan’s classification

- In this system, more weightage is given to cladistic information in comparison to phenetic information.

- This system provides classification only upto the family level, thus it is not suitable for identification and adoption in herbaria.

- Takhtajan recognised angiosperms as division which actually deserve a class rank like that of the systems of Dahlgren (1983) and Thorne (2003).

- Numerous monotypic families have been created in 1997 due to the further splitting and increase in number of families to 592 (533 in 1987), resulting into a very narrow circumscription.

- Takhtajan incorrectly suggested that smaller families are more ‘natural’.

- Although the families Winteraceae and Cancellaceae showed 99 to 100% relationship by multigene analyses, Takhtajan placed these two families in two separate orders.

A concluding remark

In his foreword to Flowering Plants (Takhtajan, Armen, 2009), American botanist & environmentalist Peter Raven wrote:

“Professor Armen Takhtajan, a giant among botanists, has spent a lifetime in the service of his science and of humanity. As a thoroughgoing internationalist, he promoted close relationships between botanists and people of all nations through the most difficult times imaginable, and succeeded with his strong and persistent personal warmth. He also has stood for excellent modern science throughout this life and taught hundreds of students to appreciate the highest values of civilization whatever their particular pursuits or views, or the problems they encountered.”

Source

- Lecture of Respected Professor Dr. Oliur Rahman, University of Dhaka. (Some of the points are paraphrased here. And many data were taken from internet. If this article has any error, only the author is to blame.)

- Armen Takhtajan from Wikipedia.

- ARMEN L. TAKHTAJAN (1910-2009) from Botanical Electronic News.

- Merits of takhtajan system of classification by Course Hero.

Revised by

- Md. Siddiq Hasan on August 12, 2020.

- Abulais Shomrat on 12 January, 2021.

Plantlet The Blogging Platform of Department of Botany, University of Dhaka

Plantlet The Blogging Platform of Department of Botany, University of Dhaka